Chapter One - The Blissful Years

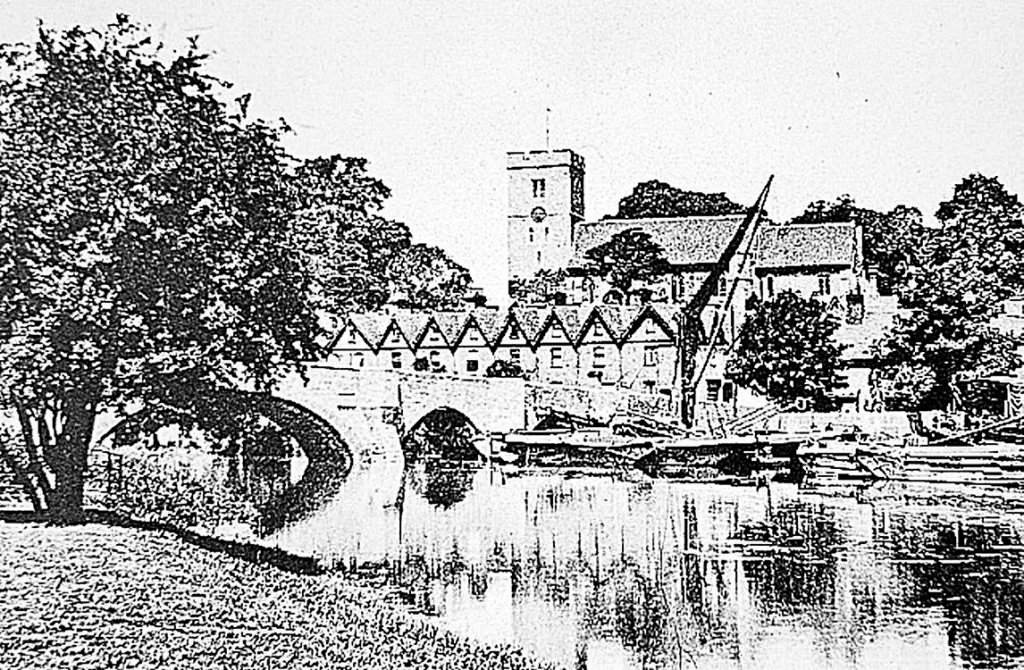

FERRYDEN is a busy little village situated on the banks of a navigable river in the heart of South East England. it is approximately four miles from the nearest town, and less than two hours journey time by road or rail from London. In the thirties, it had a population of around two thousand people, with an economy based mainly on agriculture, quarrying, and manufacturing industry. It is steeped in history, with several ancient monuments and other places of interest, including a thirteenth century bridge, which is overlooked by a church of roughly the same vintage.

It also has a number of "gentlemen's residences". One of these was a hospital in the thirties, and another of some note subsequently became the home of a religious order. Like most villages in those days, it had an array of shops to cover local needs, and several public houses. It also had a bakery, a barber shop, a blacksmith, an old fashioned 'snob' [1], and a brewery. Access was by road and rail. The river, which has a seaport at its mouth, was used for commercial traffic to nearby towns and local industries.

My first recollection of things happening around me must have been at a very early age. I can remember sitting up in a pram in our front room, conscious of the warm blankets that covered me, and of a cosy feeling from the closeness of the hood and sides. The room seemed enormous, and I could see pretty ornaments on the mantelpiece and a table with an aspidistra on it near the window. Later on, I can remember playing with our pets, getting very excited about my brother George's new train set, and being taken-to hospital when I injured my left eye. I can even remember Father giving me the top of his egg as a special treat at tea time, and the young girls who admired my dimples and loved to take me out for walks on a Saturday morning.

By the mid-thirties, I attended school for the first time, and was just nine years old when war broke out. Too young to appreciate the gravity of the storm clouds gathering in Europe, but old enough to understand most of what was going on. Our family name was Wilks, and Grandfather had some claim to fame as a leading beekeeper of his day. Almost inevitably, 'Wilkie' became my 'Nickname'. I acquired this soon after I had settled down at school, and it has remained with me ever since. We had two pets - a cat called 'Tim', who followed Mother everywhere, and a little Fox Terrier bitch called 'Muffet'.

The preparations for war were taken seriously by the village community. There were meetings at the local school to advise on air raid precautions, people were recruited into the emergency services, and demonstrations were given on methods of dealing with incendiary bombs and other likely hazards. The main fear was the possibility of chemical warfare, and the villagers, including children and babies, were issued with gas masks. Looking back it all seemed very frightening, but we were blissfully unaware of the implications. The Great War seemed a lifetime away and we were far too young to comprehend or imagine the horrors that were to come.

We were more concerned about our own little world of fun and games, getting into mischief, scrumping a few apples, having enough sweets, and of course, coming home from school or play to enjoy the warmth of our own homes and Mother's cooking. In any case, war seemed little more than an adventure we had been told of or read about in comic strips, and most of us had visions of great deeds by gallant heroes who never came to any harm. There was talk of evacuation, but we felt that the adults were overreacting, and many of us were secretly looking forward to the conflict.

Those far off days inevitably generate feelings of nostalgia. In spite of the threat of war, it seemed that the summer days were long, hot and sunny. Winters, though cold and snowy, were mellowed by open coal fires, piping hot meals, and tastes that only exist in the memory. The same feelings of nostalgia linger about the cosy little rooms of the cottages which formed the heart of the village. We tend to forget that they were often draughty, poorly ventilated, and frequently suffered from rising damp.

In reality, life in the thirties was hard and very basic. Father was in his fifties and worked as a Millwright and pattern maker for an agricultural firm, earning around four pounds per week which, in those days, was considered to be a good wage. George was nine years my senior, and worked in a local box factory. Mother, who was in her forties, stayed at home to do the housework, and occasionally earned a little 'pin money', gathering fruit or picking hops.

My first venture into the hop gardens started one September morning with a ride on George's bicycle. Mother left home early to claim a bin, and gave instructions that we should follow as soon as possible after breakfast. The outward journey was uneventful, and on arrival we had a lot of fun exploring a nearby wood, pulling bines, and picking a few hops on our own. At lunch time, we made a fire and brewed some tea. This was rather smoky, but the fresh air and expended energy made it taste like nectar. We continued helping Mother after lunch, but towards the end of the day George was told to take me home and get the tea ready.

My first venture into the hop gardens started one September morning with a ride on George's bicycle. Mother left home early to claim a bin, and gave instructions that we should follow as soon as possible after breakfast. The outward journey was uneventful, and on arrival we had a lot of fun exploring a nearby wood, pulling bines, and picking a few hops on our own. At lunch time, we made a fire and brewed some tea. This was rather smoky, but the fresh air and expended energy made it taste like nectar. We continued helping Mother after lunch, but towards the end of the day George was told to take me home and get the tea ready.

The pathway out of the hop garden was very narrow, and unsuitable for bicycles. It began with a steep and rather rocky slope, and had late cereal crops on either side. For some reason, George had decided to ride down the hill with me sitting on a makeshift seat astride the crossbar. We got about halfway down, and were travelling quite fast, when the front wheel hit a large stone and he lost control. The bicycle cavorted into the air and landed in the adjoining field. The front wheel had buckled and was hidden from view, but the rear wheel was clearly visible above the cereals, spinning and free-wheeling as the mechanism ticked away.

George landed some way further down the hill in the middle of the path, and I was crying my eyes out on the verge. Unbeknown to us, a priest was using the path on that particular day as a short cut to some of his flock who lived a mile or so beyond the hop garden. He witnessed the whole incident and, as I regained my composure, I saw him wagging an admonishing finger and lecturing George. I can't remember what he said, but he looked very menacing in his black robes and clerical hat. Later on, I was told that he had been ranting at my brother for several minutes about his recklessness, and I recall his parting words as though it were yesterday. "God never meant man to travel at such great speeds" he said, and with this, he turned on his heel and stormed off without a glance in my direction.

Mother was very cross when she realised what had happened, but we were not badly hurt, and the bicycle was soon repaired. However, the lesson had been learned, and George dismounted on all future occasions when he had to negotiate that hill.

Our home in Ferryden was a 'two up, two down' terraced cottage located by a stream near the village centre. A large proportion of the houses were constructed at the turn of the century, and none of these had central heating or an indoor lavatory. The lavatories were generally located at the top of the garden, and it was not uncommon to see an old lady on a windy winter's night struggling to the toilet with a candle in a Jam jar to prevent it from blowing out. Chamber pots were a standard feature in the bedrooms, and newspaper was used for the most base of human functions.

On bath night, we had to heat water in a coal-fired copper, while Father dragged in the galvanised tub and filled it so that you could wallow luxuriously in front of the kitchen fire. On her bath night, Mother would turn everybody out, pull the curtains, and lock the doors; the rest of us never bothered. The attempts at becoming operatic tenors, or in my case a boy soprano, were usually sufficient to keep prying eyes at bay, and in any case, the kitchen table stood in the way of a 'birds eye view'.

There were many other differences with present day life, particularly with the weekly wash. No labour-saving machines in those days. The work had to be done using the wash-house copper, a deep earthenware sink, a 'wash-board', and a manually operated mangle to get rid of the excess water before it could be put on a line to dry. It was very hard work, and heaven help anyone who let smuts drift into our back yard or who happened to brush dirty hands or implements against it.

After washday it was time for ironing. This, too, was part of the drudgery. Mother never had an electric iron until the end of the decade, when she became the proud owner of a thermostatically controlled model, considered to be the last word in luxury. Until then, she had used heavy flat irons, which had to be heated on the kitchen range. Considerable skill and a modicum of spit were needed to ensure the right temperature, but in spite of what seemed a 'hit and miss' way of doing things, I never once knew her to make a mistake.

Cooking methods were labour intensive by today's standards. There were no 'fast foods' or mechanical aids, but the results were 'out of this world'. We had a primitive gas cooker in the wash house, and a kitchen range which also served as a space heater. Every week this had to be 'black-leaded' and polished. It was filthy work which, combined with all the other jobs, left the hands with a very rough and weathered appearance.

The fuel was mainly coal which was kept indoors in a cupboard under the stairs, and elm logs from fallen branches in the fields which Father had gained permission to remove. I have fond memories of dark evenings by a log fire, with George using his hands to make animal shapes on the wall, and of ghost stories which seemed to gain credibility in the firelight glow. Electricity was laid on, but used only for lighting and Mother's new iron. It was far too expensive for any other purpose.

Father, much to Mother's disgust, enjoyed a glass of beer in the local pub, and she would get very annoyed if he overran his time on a Sunday when the lunch was being dished up. Another of her 'pet hates' was his phonograph. This played cylindrical records and was my first introduction to light classical music. To avoid annoying Mother, we often 'sought refuge' in a very large and specially constructed cupboard, where we spent many happy hours listening to ballads, songs, and operatic arias from the Victorian era.

Entertainment was largely provided within the home, but we enjoyed an occasional trip to the local town cinemas and, as a very rare treat, a visit to one of the London shows. Cards and board games were frequently played, and we had a radio which Father made himself from a kit. This was a splendid set which served us well for more than twenty years. Television had just made its appearance, and was demonstrated in the village, but only the very rich could afford it. Transmissions were stopped altogether when the war broke out, and did not resume until sometime after hostilities had ceased. November the fifth was a time we all looked forward to, and for the princely sum of £1, George would buy enough fireworks to fill a tea chest.

The health care and social services etc. that we take for granted today were virtually non-existent. Most families made provision for illness or emergency by paying into a local club or friendly society, although one or two things were provided by the state. For example, a basic education to the age of fourteen, free milk for the younger children and, of course, a somewhat meagre old age pension.

Law and order were maintained by the village 'Bobby' (P.C. Hatfield). He was a dedicated man who patrolled the streets on a 'push-bike' and spent much of his time on point duty at the foot of the bridge. He lived in the village, was regarded as a friend by most of the villagers, and carried out his duties with discretion. Minor offences were treated leniently, and he would only take action when forced to. Warnings and a record in the note book were usually sufficient to deter most offenders. Where we were concerned, it was a clip round the ear or, far worse, a threat to involve our parents.

The trust and understanding that P.C. Hatfield built up did much to maintain 'the peace', and villagers would always be on hand if needed. I can recall one occasion when he stumbled on a crime as it was being committed. Although at a considerable disadvantage, he did not hesitate to confront the felons, and was badly beaten up. A wave of anger swept through the village, and he was given a lot of help, which eventually played a significant part in tracking the culprits down.

Much of a policeman's work is routine, but it does have its lighter moments, as it did one Sunday evening when a frantic villager approached P. C. Hatfield as he was directing traffic. "There's a woman in a flat just down the road" he shouted, "and she's hanging out of the window screaming that her husband is murdering her". The constable stroked his chin for a moment and looked thoughtful. "Has he done it yet?" he asked. "Why, no!" said the villager, hesitantly. "Well I can't do anything about it until he does!" exclaimed the constable, and carried on directing the traffic. The villager looked dumbfounded and walked away in disbelief, much to the amusement of a few bystanders who had witnessed the whole thing. Fortunately, it turned out to be a 'domestic quarrel', and no one came to any harm. I hate to think what the outcome would have been had there really been a murder.

Secondary education was open to those who could afford it, or were able enough to win a scholarship, and you could sometimes get extra help from charities who provided educational grants to 'the poor and needy'. The village school was very primitive, being a relic of the Victorian age. Heating was by a coke-fuelled stove which threw out a lot of heat if you were lucky enough to be fairly close, but I can remember sitting at the back of the classroom, where the ink often froze in the depths of winter. However, the standard of teaching was excellent in spite of class sizes, and most pupils had a good basic education before they left school. Discipline was firm but in the main fair, although some teachers had a few curious habits which often lead to unwanted problems.

One such occasion involved a group of older boys at assembly who were messing about with some explosive detonators 'acquired' from a local quarry. Without knowing what they had, one of the masters insisted (in spite of agitated protests) that they 'throw it on the fire'. This they did, with a resulting explosion that blew the top of the stove off, showered burning coke all over the classroom floor, and filled it with soot and smoke. The incident caused a stir throughout the school and, after that, he insisted on looking at objects very carefully before they were consigned to the flames.

The community in Ferryden was largely self-contained and insular, although people were very friendly and always willing to help one another. By today's standards that may have seemed intrusive, but it was to pay off handsomely when the realities of war came upon us. Nobody travelled long distances. The local town was about as far as most people went, and a visit to London was quite an adventure. Scotland, Wales and Ireland were far off foreign lands – places you dreamt of, or read about in books. Most goods and services were obtained within walking distance of home. There were no such things as supermarkets, the week's provisions being purchased from shops in the village or from roundsmen.

Most of the villagers were keen gardeners. Father had two or three allotment plots, and grew his own soft fruit, vegetables and flowers. Runner beans were his speciality, and he developed a strain of his own by saving selected seeds from year to year. I had my own little plot, indulging in a passion for growing Sweet Williams and digging holes to Australia. In spite of some strenuous efforts, I never got more than five feet down, and eventually gave it up as a bad job.

Fruit and vegetables out of season were a problem unless you were lucky enough to have made your own preserves. We never had a fridge, and domestic deep freezers were unheard of. Milk and eggs could be collected from the local dairy, which in turn was supplied by a nearby farm. I have fond memories of the many hours we spent as boys in the dairyman's stables, where we helped his son Eric Daley with the ponies. There were two - one named "Cobbler", who was getting on in years, and a much younger horse called "Trigger". We helped to 'muck' them out, make up their straw beds, prepare their food, and harness one of them to a float for the evening's milk run. It was hard work, but we loved every minute of it. Our reward was a trip to the farm, where we collected the milk in churns and delivered it to the dairy.

Sunday was a day of rest except for Mother, who always prepared a delicious roast meal, and Father, who tended his garden. Everything was homemade, and the menus were a joy to behold. We had roast beef, pork, or lamb on a Sunday, with chicken or goose as a luxury at Christmas. Rabbit pie, liver and bacon, and cottage pie were weekday favourites, supplemented with meat pies and puddings which had a wonderful flavour.

Another delicacy was the first picking of Father's broad beans, bacon, and new potatoes. Mother would cook a good helping for supper, and pour the surplus bacon fat over the potatoes and beans. It was a simple meal that was absolutely mouth-watering. Desserts, which included apple pies and puddings, blackcurrant puddings, treacle sponges, 'roly-poly' and bread and butter puddings, were all served in generous proportions.

Mushrooms were gathered from the fields, and every year we would collect nuts from the woodlands and fruit from the hedgerows. Home-made horseradish sauce was another favourite. When made up it had a delicious flavour, but was so hot that you had to use it sparingly to avoid 'blowing your head off'. We had very little money but we lived well, and I can never remember feeling hungry.

The pace of life was much slower than it is today. Short distances would be covered on foot, and bicycles were the most popular form of transport. If you wanted to go any distance, it was by bus, coach or train. The motor car was a luxury that most people dreamed about but never thought they would own. Horses were in common use, with a few motor vehicles which would rumble through the village now and then. Every week the draymen would deliver beer to the local pubs using carts hauled by magnificent white stallions. The greengrocer delivered on Saturday with a horse and cart, and the milkman used a horse drawn float every day.

Traffic was never seen as the danger it is today. We walked to school, and had complete freedom to go where the fancy took us. Our mothers warned us not to go near the river without supervision, but otherwise never worried because they knew that we would be safe. Dogs wandered freely about the streets, and the cats had a fine old time on the roofs of sheds and other buildings erected in the back gardens.

Roads were maintained by the local council, who would tar and grit them in the summer. Tar was heated in special boilers fuelled by coal or wood, the viscous liquid, being spread and gritted before consolidation by heavy steam rollers. We all enjoyed watching the procedure, and Father insisted that the smell of hot tar was good for the lungs. I particularly liked to see the steam rollers take on water from the stream near our house. The driver would stop and lower a hose into the water before starting a pump. It took about ten minutes to fill up, and we were able to inspect the machinery at close quarters and sometimes clamber up into the driver's seat. When the tanks were full, the engine would rumble away, belching smoke and dropping a few hot coals from the firebox as she went. It really was a splendid sight.

The rivers, too, were in far greater use than they are today, with steam tugboats regularly hauling a string of barges. The goods ranged from beer in barrels to huge stones, or sand, from the local quarries. One of my favourite pastimes was to walk along the river bank and watch the bargemen negotiate difficult stretches of water at speed. They used to lean on the helm at such acute angles, and steer so close to bridge piers, that it was a miracle they never fell into the river or suffered a collision.

Horses were used on the farms for ploughing and reaping, supplemented with the occasional tractor, and sometimes a steam plough. At harvest time, steam traction engines were extensively used to drive the threshing machines, whilst sheaves of corn were fed in by hand. It was thirsty work, and the farm hands needed constant refreshment in the form of beer or cider, which the farmer usually provided free of charge. Hops were picked by hand, and it was a favourite pastime of Londoners to spend their holidays on the farms in specially provided living quarters or huts. Needless to say, harvest was a time for rejoicing. There was music, dancing and plenty to eat and drink. The people were happy, and churches were full. Father used to say that harvest gave him a warm feeling, and that permeated throughout the family. It was a lovely time that we all enjoyed.

Feeding the animals was not difficult. Muffet lived on generous scraps from the table, biscuits, and an ample supply of bones from a friendly butcher. Tim also enjoyed scraps, a daily saucer of milk, all the mice he could catch, and occasionally fresh fish caught in the rivers and ponds. I well remember the reception I used to get on returning with the days catch of Roach or Bream. There were never less than a dozen hungry cats (including Tim) waiting for their supper. The noise they made clambering over the tin roofs, and the speed of movement as they secured a fish, was almost unbelievable. The whole catch would disappear in a matter of seconds, followed by crunching noises from nearby bushes, and 'swearing' that would make a trooper blush.

This, then, was a snapshot of life in Ferryden as it seemed in those far off days before the war. A basic but relatively carefree existence, where the pace of life gave plenty of time for everyone to 'stand and stare'. The villagers worked hard, for very little money, but apart from the necessities of life there was little to spend it on. Pleasures were simple, and they entertained themselves. There were few, if any, pressures to 'keep up with the Joneses', and if you wanted something you waited until you had enough money to pay for it.

The motor car and the complicated lifestyles we have today were little more than a fantasy. These were days when you could hear the birds sing, listen to the bees buzzing, chase the dragonflies, and smell the sweetness of new mown hay and the scent of wild flowers. You could look to the heavens at night and see the stars flashing like diamonds. On a summer evening the swifts and swallows would grace the sky looking for insects on the wing, and the bats would squeak and flutter as the sun settled below the horizon.

The village was set in open countryside, with sheep and cows in meadows interspersed with apple, cherry, and plum orchards, and a river meandering on its journey to the sea. In the distance were hills topped with woodlands, and come spring, tinted with bluebells. Above all, there was peace and quiet, and Sunday was special. We were poor in economic terms, but rich in happiness and the quality of our environment. Little did we then know that this would change so dramatically in the years to come.

[1] shoemaker and repairer